- Home

- Richard Bach

A Gift of Wings

A Gift of Wings Read online

A Gift of Wings

The joy of flight.

The magic of flight.

The meaning of flight.

The endless challenge and

infinite rewards of flight.

This is what Richard Bach writes about.

For all who wish to rise above their earth-bound existences to feast on the freedom and adventure that Richard Bach knows and loves and recreates so magnificently, this book offers—

A Gift of Wings

Editor’s note

When I wrote Richard Bach the letter that resulted in the publication of Jonathan Livingston Seagull, I knew him very well, although I had never met him in person or spoken to him or written him before. I had read his first novel, Stranger to the Ground, and those 173 pages with him in a jet fighter plane over Europe told me enough to make me write, more than six years later, “I have a very special feeling that you could do a work of fiction that would somehow speak for the next few decades.…”

There is a lot about flying in this book, but much more about Richard Bach and his last fifteen years of seeking answers and finding some. For anyone who cares to know who he is, it is all here. The reminiscences and stories were arranged by the author for pace and enjoyment in reading; they are not in chronological order. For the reader who wants to place this life in sequence, the last pages of the book record the year each story was written.

E.F.

A DELL/ELEANOR FRIEDE BOOK

Published by

Dell Publishing

a division of

Random House, Inc.

1540 Broadway

New York, N.Y. 10036

Portions of this book appeared previously in Flying (Ziff-Davis Publishing Company), Air Progress (Slawson Communications, Inc.), Private Pilot (Peterson Publishing Company), Argosy (Popular Publications, Inc.), Sport Flying, and Air Facts.

“Across the country on an oil pressure gage” originally appeared as

“Westward the—What kind of airplane is that anyway?” Copyright ©

1964 by Ziff-Davis Publishing Company. “Think black” Copyright ©

1962 by Ziff-Davis Publishing Company. Both reprinted by permission of Flying magazine and the Ziff-Davis Publishing Company.

Copyright © 1974 by Alternate Futures Inc., PSP

Excerpts from WIND, SAND AND STARS and THE LITTLE PRINCE by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry are used by permission of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Delacorte Press, New York, New York, excepting brief quotes used in connection with reviews written specifically for inclusion in a magazine or newspaper.

The trademark Dell® is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

eISBN: 978-0-307-82434-9

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Editor’s note

Title Page

Copyright

It is said that we have ten seconds

People who fly

I’ve never heard the wind

I shot down the Red Baron, and so what

Prayers

Return of a lost pilot

Words

Across the country on an oil pressure gage

There’s always the sky

Steel, aluminum, nuts and bolts

The girl from a long time ago

Adrift at Kennedy airport

Perspective

The pleasure of their company

A light in the toolbox

Anywhere is okay

Too many dumb pilots

Think black

Found at Pharisee

School for perfection

South to Toronto

Cat

Tower 0400

The snowflake and the dinosaur

MMRRrrrowCHKkrelchkAUM … and the party at LaGuardia

A gospel according to Sam

A lady from Pecatonica

There’s something the matter with seagulls

Help I am a prisoner in a state of mind

Why you need an airplane … and how to get it

Aviation or flying? Take your pick

Voice in the dark

Barnstorming today

A piece of ground

Let’s not practice

Journey to a perfect place

Loops, voices, and the fear of death

The thing under the couch

The $71,000 sleeping bag

Death in the afternoon—a story of soaring

Gift to an airport kid

The dream fly-in

Egyptians are one day going to fly

Paradise is a personal thing

Home on another planet

Adventures aboard a flying summerhouse

Letter from a God-fearing man

Chronology

Other Books by This Author

It is said that we have ten seconds

when we wake of a morning, to remember what it was we dreamed the night before. Notes in the dark, eyes closed, catch bits and shards and find what the dreamer is living, and what the dreaming self would say to the self awake.

I tried that for a while with a tape recorder, talking my dreams into a little battery-powered thing by the pillow, the moment I woke. It didn’t work. I remembered for a few seconds what had happened in the night, but I could never understand later what the sounds on the tape were saying. There was only this odd croaking tomb voice, hollow and old as some crypt door, as though sleep were death itself.

A pen with paper worked better, and when I learned not to write one line on top of another, I began to know about the travels of that part of me that never sleeps at all. Lots of mountains, in dream country, lots of flying going on, lots of schools, lots of oceans plowing into high cliffs, lots of strange trivia and now and then a rare moment that might have been from a life gone by, or from one yet to be.

It wasn’t much later that I noticed that my days were dreams themselves, and just as deeply forgotten. When I couldn’t remember what happened last Wednesday, or even last Saturday, I began keeping a journal of days as well as of nights, and for a long time I was afraid that I had forgotten most of my life.

When I gathered up a few cardboard boxes of writing, though, and put together my favorite best stories of the last fifteen years into this book, I found that I hadn’t forgotten quite so much, after all. Whatever sad times bright times strange fantasies struck me as I flew, I had written—stories and articles instead of pages in a journal, several hundred of them in all. I had promised when I bought my first typewriter that I would never write about anything that didn’t matter to me, that didn’t make some difference in my life, and I’ve come pleasantly close to keeping that promise.

There are times in these pages, however, that are not very well written—I have to throw my pen across the room to keep from rewriting There’s Something the Matter with Seagulls and I’ve Never Heard the Wind, the first stories of mine to sell to any magazine. The early stories are here because something that mattered to the beginner can be seen even through the awkward writing, and in the ideas he reached for are some learning and perhaps a smile for the poor guy.

Early in the year that my Ford was repossessed, I wrote a note to me across some calendar squares where a distant-future Richard Bach might find it:

How did you survive to this day? From here it looks like a miracle was needed. Did the Jonathan Seagull book get published? Any films?

What totally unconceived new projects? Is it all better and happier? What do you think of my fears?

—RB 22 March 1968

Maybe it’s not too late to appear in a smoke puff and answer his questions.

You survived because you decided against quitting when the battle wasn’t much fun … that was the only miracle required. Yes, Jonathan finally was published. The film ideas, and a few others you hadn’t thought of, are just beginning. Please don’t waste your time worrying or being afraid.

Angels are always saying that sort of thing: don’t fret, fear not, everything’s going to be OK. Me-then would probably have frowned at me-now and said, “Easy words for you, but I’m running out of food and I’ve been broke since Tuesday!”

Maybe not, though. He was a hopeful and trusting person. Up to a point. If I tell him to change words and paragraphs, cut this and add that, he’ll ask that I get lost, please, just run along back into the future, that he knows very well how to say what he wants to say.

An old maxim says that a professional writer is an amateur who didn’t quit. Somehow, maybe because he couldn’t keep any other job for long, the awkward beginner became an unquitting amateur, and still is. I never could think of myself as a Writer, as a complicated soul who lives only for words in ink. In fact, the only time I can write is when some idea is so scarlet-fierce that it grabs me by the neck and drags me thrashing and screaming to the typewriter. I leave heel marks on the floors and fingernail scratches in the walls every inch of the way.

It took far too long to finish some of these stories. Three years to write Letter from a God-fearing Man, for instance. I’d hit that thing over and over, knowing it had to be written somehow, knowing there was a lot that mattered, that needed saying there. Forced to the typewriter, all I’d do was surround myself with heaps of crumpled paper, the way writers do in movies. I’d get up gnashing and snarling and go wrap myself around a pillow on the bed to try it longhand in a fresh notebook, a trick that sometimes works on hard stories. But the religion-of-flight idea kept coming out of my pencil the color of lead and ten times heavier and I’d mutter harsh words and crunch it up as though solemn bad writing can be crunched and thrown at a wall as easily as notebook paper.

But then one day there it was. It was the guys at the soap factory that made it work—without the crew at Vat Three who showed up out of nowhere, the story would be a wrinkled ball at some baseboard yet.

It took time to learn that the hard thing about writing is to let the story write itself, while one sits at the typewriter and does as little thinking as possible. It happened over and again, and the beginner learned—when you start puzzling over an idea, and slowing down on the keys, the writing gets worse and worse.

Adrift at Kennedy Airport comes to mind. The closest I steered to insanity was in that one story, originally planned as a book. As with Letter, the words kept swinging back to invisible dank boredom; all sorts of numbers and statistics kept appearing in the lines. It went on that way for nearly a year, days and weeks at the monster circus-airport, watching all the acts, satchels filling with popcorn research, pads of cotton-candy notes, and it all turned into gray chaff on paper.

When I decided at last that I didn’t care what the book publisher wanted and that I didn’t care what I wanted and that I was just going to go ahead and be naive and foolish and forget everything and write, that is when the story opened its eyes and started running around.

The book was rejected when the editor saw it charging across the playground without a single statistic on its back, but Air Progress printed it at once, as it was—not a book, not an article, not an essay. I don’t know whether I won or lost that round.

Anyone who would print his loves and fears and learnings on the pages of magazines says farewell to the secrets of his mind and gives them to the world. When I wrote The Pleasure of Their Company, one side of this farewell was simple and clear: “The way to know any writer is not to meet him in person, but to read what he writes.” The story put itself on paper out of a sudden realization … some of my closest friends are people I’ll never meet.

The other side of this farewell to secrets took some years to see. What can you say to a reader who walks up at an airport knowing you better than he knows his own brother? It was hard to believe that I hadn’t been confiding my inner life to a solitary typewriter, or even to a sheet of paper, but to living people who will occasionally appear and say hello. This is not all fun for one who likes lonely things like sky and aluminum and places that are quiet in the night. “HI THERE!” in what has always been a silent unseen place is a scary thing, no matter how well meant it’s said.

I’m glad now that it was too late for me to call Nevil Shute on the telephone, or Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, or Bert Stiles, when I found that I loved who they are. I could only have frightened them with my praise, forced them to build glad-you-liked-the-book walls against my intrusions. I know them better, now, for never having spoken with them or never having met them at bookstore autograph parties. I didn’t know this when The Pleasure of Their Company was written, but that’s not a bad thing … new truths fit old ones without seams or squeaks.

Most of the stories here were printed in special-interest magazines. A few thousand people might have read them and thrown them away, or dropped them off in stacks at a Boy Scout paper drive. It’s a quick world, magazine writing. Life there has the span of a May-fly’s, and death is having no stories in print at all.

The best of my paper children are here, rescued from beneath tons of trash, saved from flame and smoke, alive again, leaping from castle walls because they believe that flying is a happy thing to do. I read them today and hear myself in an empty room: “There is a lovely story, Richard!” “Now that is what I call beautiful writing!” These make me laugh, and sometimes in some places they make me cry, and I like them for doing that.

Perhaps one or two of my children might be yours, too, and take your hand and maybe help you touch the part of your home that is the sky.

—RICHARD BACH

August 1973

People who fly

For nine hundred miles, I listened to the man in the seat next to mine on Flight 224 from San Francisco to Denver. “How did I come to be a salesman?” he said. “Well, I joined the Navy when I was seventeen, in the middle of the war …” And he had gone to sea and he was in the invasion of Iwo Jima, taking troops and supplies up to the beach in a landing craft, under enemy fire. Incidents many, and details of the time, back in the days when this man had been alive.

Then in five seconds he filled me in on the twenty-three years that came after the war: “… so I got this job with the company in 1945 and I’ve been here ever since.”

We landed at Denver Stapleton and the flight was over. I said goodbye to the salesman, and we went our ways into the crowd at the terminal and of course I never saw him again. But I didn’t forget him.

He had said it in so many words—the only real life he had known, the only real friends and real adventures, the only things worth remembering and reliving since he was born were a few scattered hours at sea in the middle of a world war.

In the days that led away from Denver, I flew light airplanes into little summer fly-ins of sport pilots around the country, and I thought of the salesman often and I asked myself time and again, what do I remember? What times of real friends and real adventure and real life would I go back to and live over again?

I listened more carefully than ever to the people around me. I listened as I sat with pilots, now and then, clustered on the night grass under the wings of a hundred different airplanes. I listened as I stood with them in the sun and while we walked aimlessly, just for the sake of talking, down rows of bright-painted antiques and home-builts and sport planes on display.

“I suspect the thing that makes us fly, whatever it is, is the same thing that draws the sailor out to the sea,” I heard. “Some people will never understand why and we can’t explain it to them. If they’re willing and have an open heart we can show them, but tell them we can’t.”

It’s true. Ask “Why fly?” and I should tell you nothing. Instead, I should take you out to the grounds of an airport on a Saturday morning in the e

nd of August. There is sun and a cloud in the sky, now, and here’s a cool breeze hushing around the precision sculptures of lightplanes all washed in rainbows and set carefully on the grass. Here’s a smell of clean metal and fabric in the air, and the swishing chug of a small engine spinning a little windmill of a propeller, making ready to fly.

Come along for a moment and look at a few of the people who choose to own and fly these machines, and see what kind of people they are and why they fly and whether, because of it, they might be a little bit different than anyone else in all the world.

I give you an Air Force pilot, buffing the silver cowl of a lightplane that he flies in his off-duty hours, when his eight-engine jet bomber is silent.

“I guess I’m a lover of flying, and above all of that tremendous rapport between a man and an airplane. Not just any man—let me exclude and be romantic—but a man who feels flight as his life, who knows the sky not as work or diversion, but as home.”

Listen to a couple of pilots as one casts a critical eye on his wife in her own plane, practicing landings on the grass runway: “Sometimes I watch her when she thinks I’m gone. She kisses that plane on the spinner, before she locks the hangar at night.”

An airline captain, touching up the wing of his homebuilt racer with a miniature paint bottle and a tiny brush. “Why fly? Simple. I’m not happy unless there’s some air between me and the ground.”

In an hour, we talk with a young lady who only this morning learned that an old two-winger has been lost in a hangar fire: “I don’t think you’re ever the same after seeing the world framed by the wings of a biplane. If someone had told me a year ago that I could cry over an airplane, I would have laughed. But I had grown to love that old thing …”

Do you notice that when these people talk about why they fly and the way that they think about airplanes, not one of them mentions travel? Or saving time? Or what a great business tool this machine can be? We get the idea that those are not really so important, and not the central reason that brings men and women into the sky. They talk, when we get to know them, of friendship and joy and of beauty and love and of living, of really living, firsthand, with the rain and the wind. Ask what they remember of their life so far and not one of them will skip the last twenty-three years. Not one.

Illusions: The Adventures of a Reluctant Messiah

Illusions: The Adventures of a Reluctant Messiah Biplane

Biplane Stranger to the Ground

Stranger to the Ground A Gift of Wings

A Gift of Wings Holidays on Ice

Holidays on Ice Hypnotizing Maria: A Story

Hypnotizing Maria: A Story Jonathan Livingston Seagull

Jonathan Livingston Seagull The Bridge Across Forever: A True Love Story

The Bridge Across Forever: A True Love Story Nothing by Chance

Nothing by Chance Illusions

Illusions Jonathan Livingston Seagull: The New Complete Edition

Jonathan Livingston Seagull: The New Complete Edition Hypnotizing Maria

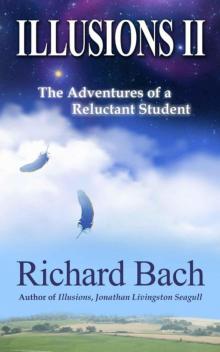

Hypnotizing Maria Illusions II: The Adventures of a Reluctant Student (Kindle Single)

Illusions II: The Adventures of a Reluctant Student (Kindle Single)